Excerpted from: A Tagore Reader, edied by Amiya Chakravarty

Tagore and Einstein met through a common friend, Dr. Mendel. Tagore visited Einstein at his residence at Kaputh in the suburbs of Berlin on July 14, 1930, and Einstein returned the call and visited Tagore at the Mendel home. Both conversations were recorded and the above photograph was taken. The July 14 conversation is reproduced here, and was originally published in The Religion of Man (George, Allen & Unwin, Ltd., London), Appendix II, pp. 222-225.

TAGORE: I was discussing with Dr. Mendel today the new mathematical discoveries which tell us that in the realm of infinitesimal atoms chance has its play; the drama of existence is not absolutely predestined in character.

EINSTEIN: The facts that make science tend toward this view do not say good-bye to causality.

TAGORE: Maybe not, yet it appears that the idea of causality is not in the elements, but that some other force builds up with them an organized universe.

EINSTEIN: One tries to understand in the higher plane how the order is. The order is there, where the big elements combine and guide existence, but in the minute elements this order is not perceptible.

TAGORE: Thus duality is in the depths of existence, the contradiction of free impulse and the directive will which works upon it and evolves an orderly scheme of things.

EINSTEIN: Modern physics would not say they are contradictory. Clouds look as one from a distance, but if you see them nearby, they show themselves as disorderly drops of water.

TAGORE: I find a parallel in human psychology. Our passions and desires are unruly, but our character subdues these elements into a harmonious whole. Does something similar to this happen in the physical world? Are the elements rebellious, dynamic with individual impulse? And is there a principle in the physical world which dominates them and puts them into an orderly organization?

EINSTEIN: Even the elements are not without statistical order; elements of radium will always maintain their specific order, now and ever onward, just as they have done all along. There is, then, a statistical order in the elements.

TAGORE: Otherwise, the drama of existence would be too desultory. It is the constant harmony of chance and determination which makes it eternally new and living.

EINSTEIN: I believe that whatever we do or live for has its causality; it is good, however, that we cannot see through to it.

TAGORE: There is in human affairs an element of elasticity also, some freedom within a small range which is for the expression of our personality. It is like the musical system in India, which is not so rigidly fixed as western music. Our composers give a certain definite outline, a system of melody and rhythmic arrangement, and within a certain limit the player can improvise upon it. He must be one with the law of that particular melody, and then he can give spontaneous expression to his musical feeling within the prescribed regulation. We praise the composer for his genius in creating a foundation along with a superstructure of melodies, but we expect from the player his own skill in the creation of variations of melodic flourish and ornamentation. In creation we follow the central law of existence, but if we do not cut ourselves adrift from it, we can have sufficient freedom within the limits of our personality for the fullest self-expression.

EINSTEIN: That is possible only when there is a strong artistic tradition in music to guide the people's mind. In Europe, music has come too far away from popular art and popular feeling and has become something like a secret art with conventions and traditions of its own.

TAGORE: You have to be absolutely obedient to this too complicated music. In India, the measure of a singer's freedom is in his own creative personality. He can sing the composer's song as his own, if he has the power creatively to assert himself in his interpretation of the general law of the melody which he is given to interpret.

EINSTEIN: It requires a very high standard of art to realize fully the great idea in the original music, so that one can make variations upon it. In our country, the variations are often prescribed.

TAGORE: If in our conduct we can follow the law of goodness, we can have real liberty of self-expression. The principle of conduct is there, but the character which makes it true and individual is our own creation. In our music there is a duality of freedom and prescribed order.

EINSTEIN: Are the words of a song also free? I mean to say, is the singer at liberty to add his own words to the song which he is singing?

TAGORE: Yes. In Bengal we have a kind of song-kirtan, we call it-which gives freedom to the singer to introduce parenthetical comments, phrases not in the original song. This occasions great enthusiasm, since the audience is constantly thrilled by some beautiful, spontaneous sentiment added by the singer.

EINSTEIN: Is the metrical form quite severe?

TAGORE: Yes, quite. You cannot exceed the limits of versification; the singer in all his variations must keep the rhythm and the time, which is fixed. In European music you have a comparative liberty with time, but not with melody.

EINSTEIN: Can the Indian music be sung without words? Can one understand a song without words?

TAGORE: Yes, we have songs with unmeaning words, sounds which just help to act as carriers of the notes. In North India, music is an independent art, not the interpretation of words and thoughts, as in Bengal. The music is very intricate and subtle and is a complete world of melody by itself.

EINSTEIN: Is it not polyphonic?

TAGORE: Instruments are used, not for harmony, but for keeping time and adding to the volume and depth. Has melody suffered in your music by the imposition of harmony?

EINSTEIN: Sometimes it does suffer very much. Sometimes the harmony swallows up the melody altogether.

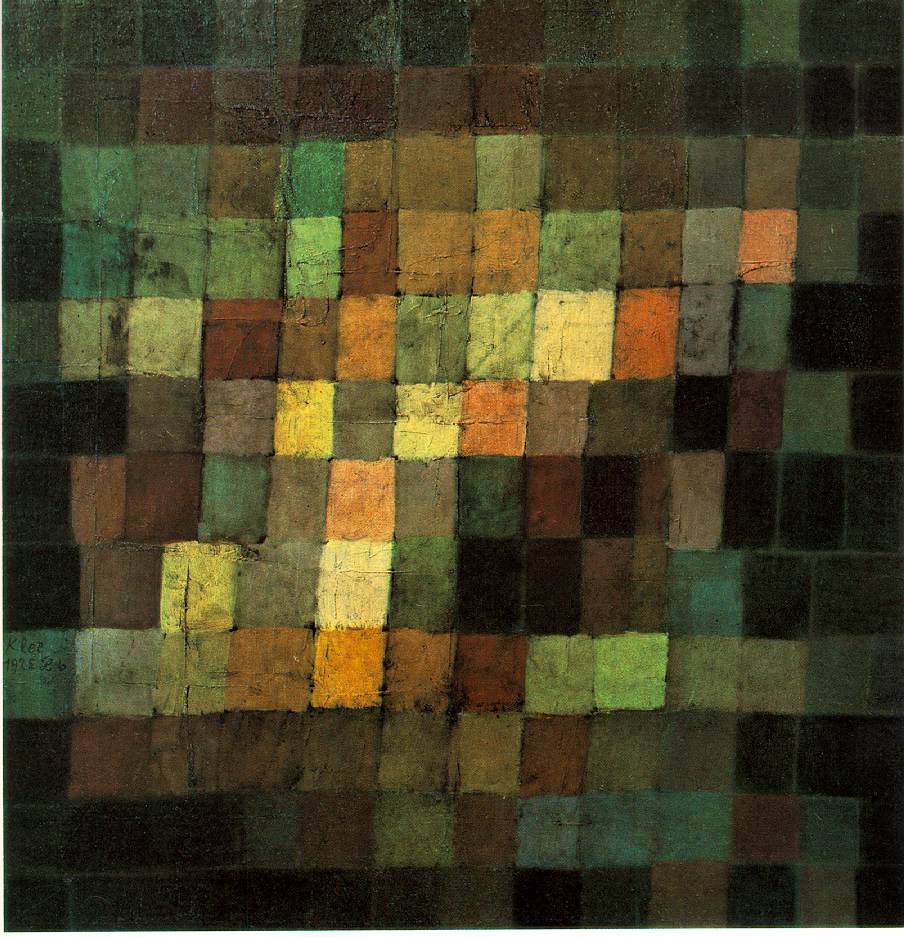

TAGORE: Melody and harmony are like lines and colors in pictures. A simple linear picture may be completely beautiful; the introduction of color may make it vague and insignificant. Yet color may, by combination with lines, create great pictures, so long as it does not smother and destroy their value.

EINSTEIN: It is a beautiful comparison; line is also much older than color. It seems that your melody is much richer in structure than ours. Japanese music also seems to be so.

TAGORE: It is difficult to analyze the effect of eastern and western music on our minds. I am deeply moved by the western music; I feel that it is great, that it is vast in its structure and grand in its composition. Our own music touches me more deeply by its fundamental lyrical appeal. European music is epic in character; it has a broad background and is Gothic in its structure.

EINSTEIN: This is a question we Europeans cannot properly answer, we are so used to our own music. We want to know whether our own music is a conventional or a fundamental human feeling, whether to feel consonance and dissonance is natural, or a convention which we accept.

TAGORE: Somehow the piano confounds me. The violin pleases me much more.

EINSTEIN: It would be interesting to study the effects of European music on an Indian who had never heard it when he was young.

TAGORE: Once I asked an English musician to analyze for me some classical music, and explain to me what elements make for the beauty of the piece.

EINSTEIN: The difficulty is that the really good music, whether of the East or of the West, cannot be analyzed.

TAGORE: Yes, and what deeply affects the hearer is beyond himself.

EINSTEIN: The same uncertainty will always be there about everything fundamental in our experience, in our reaction to art, whether in Europe or in Asia. Even the red flower I see before me on your table may not be the same to you and me.

TAGORE: And yet there is always going on the process of reconciliation between them, the individual taste conforming to the universal standard.