TERPSICHORE

the muse of dance, and Thalia (comedy) and Melpomene (tragedy) , the muses of drama, are going to have to duke it out this month, because I'm claiming Canadian writing/directing wonder Robert Lepage as one of dance's own. To my delight, Lepage, after a three-year absence, is bringing his Andersen Project to Cal Performances late in May, to be performed by Yves Jacques. Lepage's fans have missed him.

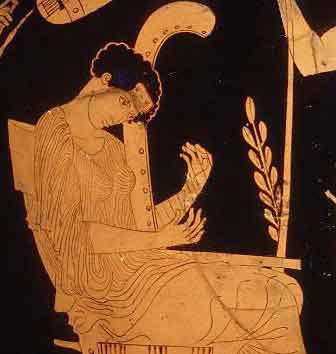

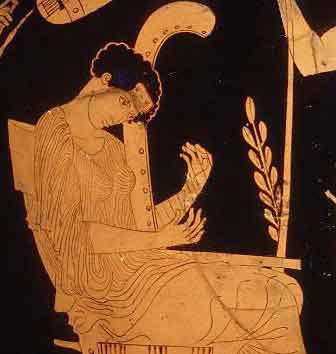

Dance, as you may know, is the real mother of Western drama, an art form that evolved in ancient Greece from Dionysian ritual performed in remote groves by raucous women who chanted, danced, worshiped, sacrificed animals and are said to have engaged in a fair amount of screeching on behalf of the god of wine and the underworld.

The goings-on apparently gave men down in the valleys a bit of a fright, and before long, the Athenians were building amphitheaters and employing participants in far more stage-managed rituals, ones that excluded women altogether. That tamed practice is the precursor to our sitcoms and daily soap operas, as well as our Broadway plays, while Jerry Springer may be the one putting us back in touch with the bestial aspects of the arts' roots.

Dance and drama are intertwined in other ways. Both depend on the body as their instrument —— the primary language for each is the physical expressiveness of the human form.

This is Lepage's metier. But the guy from up north likes to create disruption in the landscape. Lepage breaks down boundaries and injects surprises, while keeping the body at the center of his story. Perhaps that is why he calls his production company Ex Machina, from drama's "deus ex machina," meaning "god from a machine" (referring to the ancient method of using a crane to deposit actors on the Greek stage).

Although based on two tales by Hans Christian Andersen, the Andersen Project is a postmodern quest and a pensee about a solitary man confronting identity, art and history.

As usual, Lepage's visual mastery is paramount, the stage a dreamscape of projections, of movement and static figuration, and of layered light on the solitary body that at times creates a loneliness so beautiful it no longer counts as mere loneliness. And if that isn't enough, the landscape is pierced by hilarious monologues that dance their own dance.

Details: Robert Lepage's Andersen Project, 8 p.m. May 28-30, 3 p.m. June 1, Cal Performances, Zellerbach Hall, Bancroft Way at Telegraph Avenue, Berkeley, $62, 510-642-9988, www.calperfs.berkeley.edu.

THE BODY POLITIC: This month, ODC Theater in San Francisco continues the series called "For the Record: Dancers Debate the Body Politic" in its temporary digs at Theater Artaud. May 1-3 spotlights veteran choreographer and the unsung Bacchante of Bay Area experimentation, Sara Shelton Mann, who founded Contraband in the mid-'80s, a dance troupe that often seemed to double as a social movement.

jim bostick, the reclining bacchante

This month, she completes her three-year work-in-the-making, "Inspirare," reprising part one, "Telios Telios," from 2006, part two, "Inspirare" from 2007, and debuting part three, "RedGoldSky." Shelton Mann incorporates the "total theater" principles of her mentor Alwin Nikolai, the long lines of Cunningham dance style, with ritual elements and collage (for a sneak peek, go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=Php7hayunLU).

Mann is followed at Artaud May 8-10 by ex-Bay Area resident Miguel Gutierrez, who is now a fixture in the Brooklyn, N.Y., dance scene. He is a dancer who has invited viewers into his living room to watch him with an intimacy rarely possible in traditional spaces.

For this run, Guttieriez presents "Seduction of Order," a work that contends with the beauty and the politics of the body and is set up as a diptych that is said to address both the act of performance as well as the experience of the performance. (It sounds a little like looking into dressing room mirrors that reflect each other without end.)

Details: Sara Shelton Mann, 8 p.m. May 1-3; Miguel Gutierrez, "Seduction of Order," 8 p.m. May 8-10, Project Artaud Theater, 450 Florida St., S.F., $20 advance, $25 at the door. ODC Box Office: 415-863-9834 (2-5 p.m. Wednesdays-Saturdays). ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., S.F.

THARP PREMIERE: For pure dance, dance without a bow to ritual, to words, to allusions to grand drama, Company C Contemporary Ballet's world premiere of a Twyla Tharp dance, "Armenia," at the Dean Lesher this month is a paean to nothing but the genius of a body in motion. Tharp's 14-minute elegantly floor-skimming work has all the carefree ease of signature Tharp with Rubik's Cube intricacy hiding inside. Director Charles Anderson includes his own "Echoes of Innocence," the late Michael Smuin's "Starshadows" and former Taylor dancer David Grenke's "Vespers" on the bill.

Details: Company C, 8 p.m. May 23 and 24, Lesher Center for the Arts, Civic Drive at Locust Street, Walnut Creek. $40 general, $25 students/seniors, 925-943-7469, www.companycballet.org.

THE "IZZIES": And finally, a fine way to usher in May with Terpsichore on your arm is to sample the Isadora Duncan Awards, where more than 40 dancers, dancemakers, technicians, composers, dance companies and ensembles have been nominated for an Izzie in recognition of their outstanding achievement during 2007. It is the one time a year when the dance community turns out in all its wacky splendor to celebrate itself on the eve of National Dance Week, the week when free dance classes are held in studios, universities and colleges all around the Bay.

It's free and open to the public, reception at 6 p.m., awards ceremony at 7 p.m. Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Forum, 701 Mission St., San Francisco, 415-920-9181.

Ann Murphy's In Step appears monthly in Weekend Preview. Reach her at writingdance@yahoo.com.